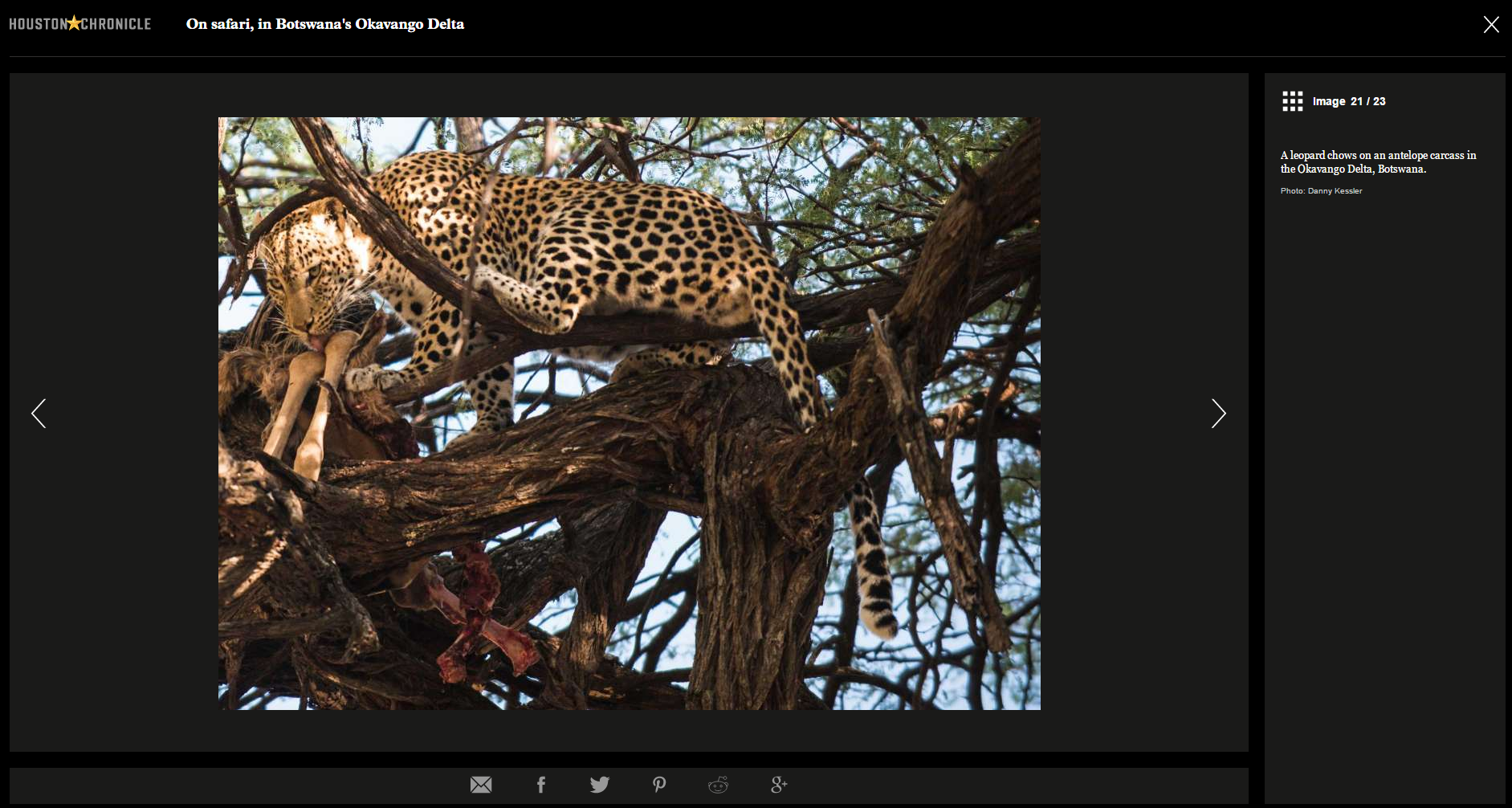

A leopard spotted in the wild during a safari trip courtesy of Little Machaba Camp, Okavango Delta, Botswana Photo: Danny Kessler

On safari, in Botswana’s Okavango Delta

Adventurers journey to Botswana for chance to glimpse wildlife in the wild kingdom

By Andrew Sessa – July 8, 2016

“Shhhhh.”

Our safari lodge’s guide Moreri Ndana puts a finger to his lips, cuts the engine of the dun-colored, open-top Land Rover and turns his head slightly.

He listens, watches, waits.

Wind whispers through the acacia trees, low grasses and tall reeds, while birds cry across the blue skies that hang over this dry flood plain in the Okavango Delta’s Moremi Game Preserve, a nearly million-acre wildlife park in the northwest corner of Botswana.

I’m on a four-day trip to the Okavango with my husband, Brian, the fourth African safari of my life, but the first of his. I’d wanted to bring him to the Delta – a vibrant and verdant expanse where the waters of the Okavango River fan out across thousands of square miles before disappearing into the Kalahari Desert – after hearing it praised for years for the diversity and density of the wildlife that fills its range of landscapes. The marshes, rivers, lagoons, islands and flood plains attract the most attention, but the dense forest, grasslands and bush of its drier eastern edges, where we are now, have much to recommend them, too. Everywhere, a ready supply of water supports large populations of animals.

Soon after Ndana silences the 4×4, we hear it: the distinctive bass note of a lion’s call, more rumble than roar. We continue our stalking, driving up and over a sandy hillock covered with low trees, their large, waxy leaves so dense that we don’t see a herd of elephants till we’re almost in the middle of it. But before they have a chance to charge us, Ndana revs the engine and we speed away.

Stopped again by a watering hole where an elephant dips his trunk to drink as the sun sets, we hear the lion once more. Dusk has come, however, and the park is closing. We’ll leave lionless tonight, but, to my surprise, I don’t mind.

One of the great pleasures of a safari, I realize, is the anticipation of a wildlife sighting, the sense that you never know what’s around the next bend in the road, or lurking behind the next copse of trees. On safari, every moment is filled with possibility.

Delta rising

But make no mistake: We had come to the Delta to see animals, not just to anticipate seeing them. We wouldn’t be disappointed.

“The Okavango is really special,” I’m told that night by Elke Malan, manager of Little Machaba, the four-tent camp where we stayed. “It’s paradise for animals because there’s always water around, so there’s always something to eat.” And where there’s always something to eat, there’s always something eating – large mammals, not least hippos and elephants, plus antelope, baboons, Cape buffalo, giraffe, zebra, and, of course, big cats who find in the Delta a veritable smorgasbord of prey.

We found Machaba thanks to Micato Safaris, the outfitter that arranged our trip. Micato’s Africa experts knew the lodge from its original, 3-year-old 10-tent site, and recommended this months-old outpost for its similarly classic 1950s safari style. Machaba sits in the Khwai Community Concession, a 445,000-acre private reserve that – unlike the adjacent government-run Moremi and Chobe national parks – allows vehicles to drive after dark and to off-road, the better for animal tracking.

Private reserves and canvas-covered accommodations are two of the enticements that make the Delta special. “The carefully monitored wildlife concessions require that camps can be taken down relatively quickly and leave only footprints,” explains Micato’s southern Africa specialist Andrea Dobbe. “So the lodges tend to be tented, which make Botswana wonderful.” Micato managing director Dennis Pinto, agrees, adding, “The diversity of activities – dugout canoes, speedboats, nature walks – let you see animals from both land and water.”

Lately, the Okavango has seen fresh growth in accommodations. Major safari players &Beyond, Belmond, Desert & Delta, Great Plains Conservation, Sanctuary and Wilderness have opened or redone properties, or announced plans to, and the company behind Machaba will debut Gomoti Plains Camp in the Delta’s wetter midsection later in 2016. This March, meanwhile, Okavango access improved, with Airlink starting five-time-a-week nonstop flights between Cape Town and Maun, the main gateway to the Delta. All of which makes now a particularly good time to go.

Hot pursuit, cool cats

From previous trips, I knew an African safari shouldn’t be about rushing through animal checklists and wildlife chases, but would be best if we let ourselves look, listen and linger, to really appreciate each wildlife encounter.

That lion hunt, however, made me see that a safari – the word means “journey” in Swahili – could satisfy with the thrill of the chase, even if we didn’t get that check mark.

Not that there’s anything wrong with a check mark. And this trip would have many.

Our time in the Okavango began with Brian making a rookie mistake, failing to pull out his camera for the drive from Khwai’s airstrip. As soon as we rounded the first turn, a massive pachyderm appeared squarely in our path – so big that both tail and trunk disappeared into the green bushes on either side of the dirt track. Lesson learned: On safari, you’re always on a game drive.

That first day ended with a wild African dog chase as Ndana careened around curves to get us to the elusive, endangered canines. (The dogs now number fewer than 7,000.) We found the big-eared, black-spotted bruisers walking along the road, and we trailed them as their brown-and-white fur turned golden in the setting sun.

On these twice-daily game drives, looking and lingering let us see animal behavior we might have missed: a troupe of baboons grooming each other in the grass; a black-and-white saddle-billed stork using its long beak to hunt for fish and frogs in a small pool; male impalas “pronking,” kicking their hind legs up in an impressive display of fitness; hyena mothers greeting their young when they returned to the den after dark; a lone male elephant bracing himself against a tree, then shaking it to bring fruit down from upper branches.

That we were able to see all this speaks volumes about the focus on conservation in Botswana, which celebrates the 50th anniversary of its independence from Great Britain this year. The government has recently banned commercial hunting and strengthened anti-poaching efforts, and it protects some 25 percent of the country’s land as wildlife reserves.

A last lingering look

By our final game drive, we still hadn’t seen that lion – though we’d continued hearing his rumbling roars, and those of his brethren, from camp. Ndana could tell the guests were getting restless.

We began the day with another rare wild dog sighting, watching a pack of well-sated pups pad around by a river, the fur on their necks tinted crimson from the blood of whatever they’d feasted on overnight, but we soon pulled away in pursuit of a leopard that another guide had spotted.

As Ndana slowly made his way around a thicket, I scanned for signs of feline life. Black spots on a tawny background appeared wherever the sun glinted on golden-hued grasses against shadowy shrubs. Camouflage might have kept the leopard hidden, but it also made me see it everywhere.

And, then, suddenly, there it was, stretched out long and lean under a hollow bush. Muscles rippled under short fur, long white whiskers twitched, head and shoulders took an almost regal posture.

Standing up, the cat stalked out of sight. We followed, circling the thicket, and, to our amazement, found not one leopard but two on the other side, the second laying by a desiccated fallen tree. We moved in closer, cameras out, clicking away. The cat cocked its head, flattened its ears and bared its teeth.

There’s the thrill of the chase, to be sure, but that’s nothing compared with the adrenaline surge you feel when an animal sees you as more foe than friend, more potential prey than passive passenger. My heart beat faster. I lowered my camera, moved back in my seat, tried not to make eye contact. But I couldn’t tear my gaze away, not then, and not when the cat stood up, bounced up a tree in quick, graceful leaps and began tearing at an antelope carcass it had stashed in the branches – one more behavior souvenir for the road.

That night, when I closed my eyes to go to sleep, I could still hear the sound of it chewing and, on the inside of my eyelids, I saw the leopard’s amber-green eyes staring back at me.